Xenia Delieza

MONITORING KPG EXAMINER

CONDUCT

Abstract

This paper

presents a research project launched through

the RCeL in 2005,[1]

with a view to monitoring the

KPG

oral

test

in English by collecting information

concerning test administration, task content

and test procedure validity, examiner

efficiency, assessment criteria validity,

and

intra- and

inter-rater

reliability. The data and findings discussed

here concern the oral tests at B2 and C1

level, which are briefly described before

the rationale behind this project and the

methodology followed – a fully structured

observation procedure – are presented. The

paper also explains the choices regarding

the participants, and the tools

developed for the purpose of data

collection. Finally, findings are discussed

along with implications of the study and

steps to be taken in the near future.

Keywords:

Monitoring, interlocutor, rater,

observation, evaluation, assessment,

feedback, training

1. Introduction

Oral proficiency interviews have often been

investigated as highly subjective processes

of assessment whereby many different factors

interplay in the production of the final

outcome. Being part of a new high-stakes

proficiency examination battery first

administered in 2004, the KPG oral test in

English was in need of thorough, real-time

investigation in terms of both the procedure

itself and the participants in it.

Observation of actual oral examinations on

the basis of structured observation forms

was proposed and finally decided as an

effective method for research into the

different aspects of the exam. Therefore, an

observation or monitoring project was

launched, which has been carried out in six

phases so far and is on-going, following the

needs of the test designers and

administrators. The observation forms used

in the various phases have been adapted and

re-adapted, according to findings from

previous phases and requirements for

research in each phase. Thus, the

observation project as a whole has produced

a wealth of information and data which have

substantially contributed in the improvement

of the test, as well as in the monitoring

and training of oral examiners (Karavas &

Delieza 2009).

This article presents the first two phases

of the observation project which were

conducted in piloting mode and were

different in focus. The first phase

investigated the test in a more global sense

looking at issues of organisation, test

procedure and examiner conduct; the second

phase was more focused on the role of the

examiner as interlocutor, i.e. while

conducting the test, and the ways in which

s/he may intervene in the candidate’s effort

for language production. On the basis of

these two phases, even more research was

done, especially on the role of the examiner

in the following phases, the results of

which have proved invaluable for the

training of oral examiners until today.

Thus, this paper presents the two basic test

levels of the KPG exams, as these were

structured in 2005-6, (because the B2 level

exam has been integrated with the B1 since

May 2011, and the C1 level exam has been

integrated with the C2 as of November 2013)

and explains the rationale for the launching

of the whole observation project, the way it

was designed and, finally, its two first

phases and the results from the analysis of

the observation tools used. Emphasis is

placed on the examiners and the ways they

conduct the exam which may affect the

candidates’ production, as factors which may

ensure or threaten the reliability and

validity of the oral test.

2. The

KPG oral test in English

The KPG oral test involves two examiners and

two candidates in the examination room. One

of the two examiners is the ‘interlocutor’,

i.e. the one who conducts the test (asks the

questions, assigns the tasks and

participates in the speech event). The other

examiner is the ‘rater’, i.e. the one who

sits nearby silently, observes the

examination and rates the candidates’

performance. The interlocutor also rates

candidates’ performance, but only after they

have left the room. The two examiners

alternate the roles of interlocutor and

rater every three or four testing sessions.

Examiners are trained in advance for their

roles as interlocutor and rater, and are

reminded about what they have to do by

guidelines in the Examiner Pack,

given to them at least two hours before the

exam begins. (The Examiner Pack also

contains the oral tasks.) At the same time,

they are given the Candidate Booklet,

which contains the prompts for the test

(photos and/or Greek texts). The examiners

are instructed to: a) explain the test

procedure and set the scene, b) use/read

task rubrics and not paraphrase or provide

their own rubrics or assign their own tasks,

c) maintain their profile as listeners in

the speech event, allowing candidates to use

all the time they have available to produce

continuous and coherent speech, and d)

intervene and/or interrupt candidates only

in certain cases (as set out in the Examiner Pack).

2.1 The B2 level

oral test

The B2 level oral test consists of three

activities (Table 1). In Activity 1, which

is a type of informal interview, the

interlocutor asks the candidates, in turn,

two to four questions about themselves,

their family and friends, their experiences,

and their future plans. In other words,

Activity 1 involves a dialogue. In Activity

2, during which the candidates are expected

to produce one-sided talk, the interlocutor

shows each candidate one or two photographs,

reads out task instructions, and asks

her/him to carry out a task. Finally, in

Activity 3, the interlocutor gives each

candidate a Greek text and time to read it

quickly. The related task that s/he assigns

involves candidates in relaying information

from the Greek text into English, with a

communicative purpose in mind. Though the

two candidates always go into the

examination room in pairs, they do not

interact in any of the activities, but

rather take turns in responding to the

tasks.

|

Activity 1 |

Responding to personal questions |

(3 min. for both candidates) |

|

Activity 2 |

One sided-talk on the basis of

visual prompts |

(5 min. for both candidates) |

|

Activity 3 |

Oral mediation on the basis of

the Greek texts |

(6 min. for both candidates) |

|

Table 1: The B2 oral test |

2.2 The C1 level oral test

The C1 level oral test

consists of two activities (Table 2). In

Activity 1, the interlocutor asks the

candidates, in turn, one opinion question,

and each has two minutes to give a full

response. In Activity 2, candidates are

provided with Greek texts which are

thematically related, or taken from the same

text source, but differ in terms of content.

The candidates are allowed about two minutes

to read these texts, once they have been

assigned a collaborative task (a task which

involves them in purposeful interaction and

negotiation in English, i.e., finding a

solution to a problem, and deciding on a

course of action, using information from the

Greek text).

|

Activity 1 |

Responding to an opinion question |

(4-5 min. for both candidates) |

|

Activity 2 |

Oral mediation on the basis of the

Greek texts |

(10-12 min. for both candidates) |

|

Table 2: The C1 oral test |

3. Rationale for the

monitoring project

One of the aims of the

project was to monitor the oral test in

English and answer a series of questions

including the following:

-

How well is the

oral test administered, and under what

conditions?

-

Which are the

most common problems encountered while the

oral test is being conducted, and

when/why/how do they surface?

-

Are the

examiners familiar with the criteria set by

the English Team?

-

Do the examiners

abide by the rules of conduct?

-

How does

following the conduct rules or deviating

from them affect candidate output?

-

Are the

assessment criteria, the marking scheme, and

the rating form valid and reliable tools?

-

Do examiners

make constructive use of the assessment

criteria, the marking scheme and the rating

form?

-

Which practices

by oral test examiners are ‘positive’ (and

should therefore be reinforced), and which

are ‘negative’ (and should therefore be

discouraged)?

These questions seek

information regarding Examiner practices.[2]

Therefore, it was decided to train observers

to

monitor the oral test process and collect

valuable information, and also evaluate

Examiner behaviour by rating a)

communicative performance, b) Examiner

conduct, and c) marking efficiency.

In

order to investigate the role of the

examiner as interlocutor and detect the ways

in which interlocutors might be influencing

the candidates’ language output, questions

relating to this role were included in the

first-phase observation forms.[3]

Since the examiners’ deviations from the

rules of conduct, such as changes to rubrics

(questions and tasks) and interruptions or

interferences, have been found to affect the

candidates’ performance (Brown 2003, 2005;

McNamara & Lumley 1997; Lazaraton 1996;

McNamara 1995, 1996, 1997; Lumley & McNamara

1995;

Young, R.

& Milanovic, M. 1992;

Ross &

Berwick 1992; Ross 1992; Bachman 1990;

van Lier 1989

among

others), the project also seeks to measure

the frequency and significance of such

deviations for the language output.

The monitoring project would also provide

information of significant use for the training

of oral examiners, because the crucial concern

behind the effort to monitor the oral test is to

make sure that examiners are consistent in the

way they conduct the test, their use of

assessment criteria, and their rating of

candidate’s performance.

Finally, few studies on

observation as a method of assessing oral

examinations in formal certification systems

have been carried out. This scheme, together

with its development for future

applications, may contribute ideas and

solutions for the investigation of oral

testing conditions and the variables or facets – as they have been referred to

in the relevant literature (Bonk & Ockey

2003; Lazaraton 2002;

Brown &

Lumley 1997;

Milanovic

& Saville 1996; McNamara 1996; Bachman et

al. 1995; Bachman 1990 among others) – which

affect the former but are generally not easy

to investigate due to the many practical

difficulties which they entail.

4. The monitoring project

design

4.1 Observation as a method

for monitoring the test and the examiners

Observation has

a long and rich history as an approach to

studying educational processes (Evertson &

Green 1986) and has been used as a research

method in many studies related to classroom

teaching and learning.[4]

However, apart from two highly influential

studies on washback – one known as the Sri

Lankan Impact Study by Wall & Alderson

(1993), and another for the IELTS exam by

Banerjee (1996) – not much has been

published as far as observation used as a

method for researching testing conditions is

concerned. In relation to evaluating an

examination itself, the best known study is

that by O’Sullivan et al. (2000). Their work

aimed at examining the construct validity of

the University of Cambridge ESOL oral tests

of general language proficiency. Since the

study required detailed and time-consuming

analyses of the language output produced

during the test, the researchers developed

checklists which could be used during actual

First Certificate in English examination

sessions, complementing other types of more

detailed analyses and applying to a larger

number of exam sessions. These checklists

comprised functions that different tasks may

elicit, and trained observers had to

recognise these functions and tick them off

every time they occurred during actual

examination sessions.

In organising the English

KPG monitoring project and observation

procedure, the Team had to take into account

various considerations which would ensure

its validity. A review of the work of other

researchers suggested that questions such as

‘Who and what is observed?’,

‘Who

is observing?’, ‘How and when?’,

and ‘What is the approach?’ were critical (Cohen, Manion & Morrison,

2000; Wallace 1998; Genesee & Upshur 1996;

Spada & Frölich 1995; Weir & Roberts 1994;

Nunan 1992; and Spada 1990).

In answering these

questions, which form the basis of

observation techniques, the following

decisions were made:

-

The twofold aim of the

monitoring

project, at its initial stages, would be to

investigate: a) how the oral test is carried

out, under what conditions and with what

limitations, and b) whether oral examiners

abide by the rules of conduct and follow the

assessment criteria.

-

The tools to be

used would be especially created observation

forms for the first two piloting phases of

the project –

one for the November 2005 B2

exam, and one for the C1 exam – and

similarly two more for the May 2006 exams

(one for each level). The latter were

constructed taking into account the results

of the November 2005 forms and it was

decided that the second phase would focus on

examiners as interlocutors.[5]

-

The observers would be examiner trainers who

had been working with the English Team.

These trainers are highly qualified

professionals who live in different parts of

the country. By using them, the problem of

observer

mobility

and

extensive training would be solved.

-

The procedure

consisted of ‘real time observations’ (cf.

Wallace, 1998). The observer was present in

the room during the time the oral test

was

being conducted, but did not intervene in

any way. In other words, the observers were

part of the live encounter and

‘documented and recorded what was happening

for research purposes’ (cf. Cohen, Manion &

Morrison, 2000: 310).

-

The format of the observation forms was

simple.

They

were

easy-to-analyse, structured checklists based

on specific categories and subcategories,

associated with rules and regulations about

test conduct. There were also a few

open-ended questions, but only when

pertaining to essential information.

4.2

Participants in the monitoring project

There were three

different categories of professionals who

took part in this project as observers: a)

KPG multipliers, i.e. examiner

trainers, who were well aware of the oral

test procedure because they train examiners

on how to conduct it, b) novice EFL teachers

taking a postgraduate course in Language

Testing and Assessment who were especially

trained for the observations (May 2006), and

c) new members of the KPG English Team and

other associates (May and November 2007).

The plan was to establish a group of

observers who would receive frequent and

systematic training and would work as

observers in all examination periods.

4.2.1 Phase 1: The November

2005 observation

During the

November 2005 examination period, 25

observers were selected by the English Team

and assigned randomly[6]

to examination centres throughout Greece to

observe how the oral test was administered

and to collect data on the basis of which

the English Team could evaluate processes,

means and results. Twenty-three of these

observers were ‘experts’ (multipliers), and

two were novices (associates). Everyone was

given detailed instructions and

over-the-phone

training on how to

conduct the observation using the forms.

Shortly after the administration of the

exams, the observers sent the completed

forms to the RCeL, where the data was

recorded, analysed, and interpreted.

The number of examiners

and candidates observed is presented in

Table 3. All in all, 236 examiners were

observed while conducting the examination,

with a total of 758 candidates. This is a

significant number of subjects since the

total number of examiners in that period was

about 500, and the total number of

candidates was about 9,500.

|

B2 |

|

Number of cases observed |

Examiners |

Candidates |

|

One examiner examining two pairs

|

97 |

388 |

|

One examiner examining one pair |

41 |

82 |

|

TOTAL |

138 |

470 |

|

C1 |

|

Number of cases observed |

Examiners |

Candidates |

|

One examiner examining two pairs |

46 |

184 |

|

One examiner examining one pair |

52 |

104 |

|

TOTAL |

98 |

288 |

4.2.2 Phase 2: The May 2006

observation

The May 2006

observation was conducted on a national

scale, just like the November 2005 project.

Thirty-three observers were selected. The

English Team had decided to use ten novice

EFL teachers taking a postgraduate course in

Language Testing and Assessment. These

students, working towards their M.A. in

Applied Linguistics at the Faculty of

English Studies of the University of Athens,

constituted the project control group, as

they had never conducted an oral test before

themselves. It was decided that they would

receive more extensive training during a

three-hour seminar.[7]

Again, the material for

the observation procedure was prepared, and

observers were instructed as to what had to

be done. Once more, the completed forms were

sent to the RCeL and the data was recorded,

analysed and interpreted.

The following tables show

the scale of the project, in terms of the

examiners and candidates observed. All in

all, 273 examiners were observed carrying

out the exam, with a total of 958

candidates. Given that the total number of

examiners used in that period was about 600

and that the total number of candidates was

about 15,000, it appears that a significant

number of subjects were observed.

|

B2 |

|

Number of cases observed |

Examiners |

Candidates |

|

One examiner examining two pairs

|

115 |

460 |

|

One examiner examining one pair |

40 |

80 |

|

TOTAL |

155 |

540 |

|

C1 |

|

Number of cases observed |

Examiners |

Candidates |

|

One examiner examining two pairs

|

89 |

356 |

|

One examiner examining one pair |

28 |

56 |

|

TOTAL |

118 |

418 |

|

Total number of examiners

observed |

273 |

|

Total number of candidates

observed |

958 |

|

Table 4: The May 2006

observation |

5. Designing the monitoring

tools

5.1 Phase 1: The November

2005 observation

The first

observation forms for levels B2 and C1 were

compiled for the November 2005 English

exams. The content of the forms was linked

to the instructions given to examiners

during training seminars and to the written

guidelines[8]

provided in the KPG Examiner Pack.

The November 2005 observation forms were

divided into two parts.

The first part (Table 5)

was a YES/NO-answer checklist (along with

space available for comments) concerning the

organisation of the examination centres in

which the oral test was conducted. It

involved questions about the examiners’ time

of arrival at the centre, the suitability of

the facilities, the availability of the

material required for examiner preparation

for the test, and the quality of the

services offered by the exam committees.

|

A. Examination Centre – Issues

of organisation |

YES |

NO |

|

1. |

Have all the examiners come to

the Centre 1½ -2 hours before

the Oral Test is due to start? |

|

|

|

2. |

Have they (and you) been given a

quiet room where there is peace

and quiet to prepare for the

Test? |

|

|

|

3. |

Have the examiners been given

the Orals material 1½ -2 hours

before the Oral Test is due to

start? |

|

|

|

4. |

Do the examiners have all the

material they need to conduct

the exam? |

|

|

|

|

a) If your answer to

question 4 is NO, please note

what was missing.

-

Candidate Booklets for examiners

…………..…………

-

Candidate Booklets for

candidates …………………….

-

Examiner packs

…………………………………………. |

|

b) How has this and other

problems and inconveniences been

dealt with by the

examiners/committee?

………………………………………………………………………… |

|

5. |

Has each pair of the examiners

been given a list with the names

of the candidates they will

examine? |

|

|

Table 5: Part 1 of the November 2005

observation form

The second part of the

form focused on questions regarding the process

of the test. The first section (Table 6)

examined whether instructions concerning seating

arrangements in the exam room were followed.

|

The setting for the Oral Test:

Have the examiners set the desks

up properly? |

YES |

NO |

|

1. |

Are the candidates sitting side

by side? |

|

|

|

2.

|

Is the Examiner-Interlocutor at

some distance from the

candidates, but sitting so that

s/he’s facing them? |

|

|

|

3.

|

Does the desk of the

Examiner-Assessor allow visual

contact with the candidates and

the Examiner-Interlocutor? |

|

|

Table 6: Part 2, Section 1 of the November

2005 observation form

The second section

consisted of two long checklists, one for

each of the two examiners. Observers were

asked to fill in each checklist in two

phases: a) while the test was being

conducted, and b) after it had been

completed, while the examiners were rating

the candidates. Finally, each observer was

expected to assess examiners for their

communicative competence and performance

during the test.

The content of the

checklists in this section of the

observation form was aimed at learning

whether the interlocutors followed the

guidelines for the exam procedure and the

rules of conduct, e.g. whether the examiners

used two or three questions for Activity 1

of B2 level, or only one question for

Activity 1 of C1 level, and whether they

took the age and general profile of each

candidate into consideration when choosing

questions, photos, texts and tasks. (Table

7).

|

Activity 1 – Dialogue |

YES |

NO |

|

3. |

Did the Examiner ask the

candidate 2-4 questions from 2-4

different categories? |

|

|

|

4. |

Did s/he take into account the

candidates’ age and other

relevant factors when s/he chose

the questions?

|

|

|

|

5. |

Did s/he interfere in any way or

interrupt the candidates while

they were trying to talk?

|

|

|

|

If this was done more than once,

briefly report how s/he did it.

…………………………………………………………………… |

|

Activity 2 – Oral

production |

YES |

NO |

|

9. |

Did s/he take into account the

candidate’s age and other

relevant factors when s/he chose

the photo(s)? |

|

|

|

10. |

Did s/he take into account the

candidate’s age and other

relevant factors when s/he chose

the task? |

|

|

|

11. |

Did s/he use the rubrics

provided? (If you say no, it

means that s/he improvised –

used his/her own rubrics) |

|

|

|

12. |

Did s/he use the exact words of

the rubrics? (If you say no, it

means that s/he accommodated to

the candidate) |

|

|

|

If you have responded NO to 11 &

12, please explain.

………………………………………………………………… |

|

13. |

Did s/he assign the task

naturally rather than read

without maintaining any eye

contact with the candidates? |

|

|

|

14. |

Did s/he interfere in any way or

interrupt candidate? |

|

|

|

If this was done more than once,

briefly report how s/he did it.

………………………………………………………………………………… |

|

15. |

Did s/he give a different

photo(s) to each candidate? |

|

|

|

16. |

Did s/he assign a different task

to each candidate? |

|

|

|

Activity 3 - Mediation |

YES |

NO |

|

20. |

Did the Examiner take into

account the candidate’s age and

other relevant factors when s/he

chose the text?

|

|

|

|

21. |

Did the Examiner take into

account the candidate’s age and

other relevant factors when s/he

chose the task?

|

|

|

|

22. |

Did s/he use the rubrics

provided? (If you say no, it

means that s/he improvised –

used his/her own rubrics) |

|

|

|

23. |

Did s/he use the exact words of

the rubrics? (If you say no, it

means that s/he accommodated to

the candidate) |

|

|

|

If you have responded NO to 22 &

23, please explain.

………………………………………………………………… |

|

24. |

Did the Examiner use a different

text with each candidate? |

|

|

|

25. |

Did the Examiner assign a

different task to each

candidate? |

|

|

Table 7: Some of the questions in Part 2,

Section 2 of the November 2005 observation

form for B2 level

Finally, there were questions on whether the

examiner’s body language and general conduct was

polite, friendly and welcoming, and also on the

marks the examiners assigned to each candidate,

which the observer had to compare to his/her

own (Table 8).

|

B2 & C1 |

|

Question |

|

1. |

When the candidates come in, does

the Examiner use appropriate

communicative strategies (e.g.,

greet them, tell them what they are

expected to do, use language and

paralanguage to make them feel

comfortable? |

|

2. |

Did the Examiner take notes in a way

that may prevent interaction, or in

a way that may work against

establishing a friendly rapport with

the candidates? |

|

13. |

Did s/he assign the task naturally

rather than read without maintaining

any eye contact with the candidates? |

|

20/

28. |

Was the Examiner’s body language

generally appropriate (polite,

friendly, welcoming, etc.)? |

Table 8: Questions related to behaviour,

attitude and body language at B2 and C1

level

5.2 Phase 2: The May 2006

observation

The usefulness and

significance of the November 2005 monitoring

project, as well as the need for more data

and evidence in issues that arose when the

first phase of the project was conducted,

rendered its continuation essential (See

Section 6 below). Thus, it was decided that

new observation forms should be created for

another monitoring project. The results of

the November 2005 project clearly indicated

the need for making a video recording of the

actual examination with a view to finding

out how changes to the instructions, or

different types of interferences or

interruptions might affect the candidates’

language output. The problem was that video

recordings were (and still are) not allowed

by Greek law during oral examination

sessions in KPG exams. In view of this

difficulty and since the November results

yielded more specific categories of

deviation on the examiners’ part, which had

to be further investigated, the original

observation forms were modified to provide

the necessary information.

Based on the results and

findings from the November 2005 project,

the new forms aimed at

finding out the different types of changes

interlocutors made to the rubrics, as well

as any kind of interferences or

interruptions. Emphasis was also given to

raising awareness of the effect these

deviations might be having on the language

output, as well as the interlocutor’s

general behaviour and its influence on the

examination process. Furthermore, the

observers were asked to write a brief report

pertaining to the examination procedures

they observed. These reports proved

particularly informative and greatly

contributed to reaching basic conclusions.

More

specifically, the May 2006 observation forms

for both

levels were divided into three

parts, and each form was designed to observe

one examiner as interlocutor with one pair of candidates.[9]

The first part of the form, which was the

longest of the three, concerned oral activities

(three in B2 and two in C1) and the way they

were conducted by the examiner. Table 9

comprises the questions (almost as they appeared

in the actual form) for B2, Activity 1. The

questions for the remaining two B2 activities,

as well as those for the two C1 activities, are

similar.

|

|

PART 1 |

|

|

Questions no:

□□□□ Questions

no:

□□□□ |

|

Candidate A |

Activity 1 - Dialogue |

Candidate B

|

|

YES |

NO |

1. Does the examiner ask 2-4

questions from 2-4 different

categories? (Circle) |

YES |

NO |

|

YES |

NO |

2. Did s/he take into account

the candidate’s age, etc. when

s/he chose the questions?

(Circle) |

YES |

NO |

|

YES |

NO |

3. Did s/he use the rubrics

provided? (Circle) |

YES |

NO |

|

YES |

NO |

4. Did s/he change or interfere

with the rubrics in any way?

(Circle) |

YES |

NO |

|

TICK

√ |

If you answer is YES, TICK (√)

below to indicate in what way

s/he did so. |

TICK

√ |

|

|

a. S/he used an introductory

question. |

|

|

|

b. S/he changed one-two words. |

|

|

|

c. S/he expanded the question. |

|

|

|

d. S/he explained the

rubric.

|

|

|

|

e. S/he repeated the rubric.

|

|

|

|

f. S/he supplied a synonym for a

word.

|

|

|

|

g. S/he used examples. |

|

|

|

h. other (Please specify)

|

|

|

TICK

√ |

5. Did s/he interrupt the

candidate or interfere with

his/her language output in order

to ... |

TICK

√ |

|

|

a. redirect the candidate

because s/he misunderstood

something? |

|

|

|

b. to help the candidate

continue by repeating his/her

last words? |

|

|

|

c. make some kind of correction? |

|

|

|

d. repeat the question or part

of it? |

|

|

|

e. supply one or more words the

candidate was unable to find? |

|

|

|

f. ask a seemingly irrelevant

question? |

|

|

|

g. add something? |

|

|

|

h. other?(Please specify)

|

|

Table 9: Part 1, Activity 1 questions (May

2006 observation form for B2 level)

In the first part of the observation form, the

observers were

also asked to judge whether the different kinds

of changes and interferences or interruptions in

all activities influenced the candidates’

language output (Table 10).

|

YES |

NO |

6. Do you think that the

interlocutor’s intervention

(change of rubric, interruption

or interference) influenced the

candidate’s language output in

any way?

If you circle YES, please

indicate if s/he made things

easier or more difficult for the

candidate and provide any useful

comments:____________________________

__________________________________________ |

YES |

NO |

Table 10: Question related to the influence

of intervention on the candidate’s language

output

The second part included

questions on the behaviour of the examiner

(Table 11). Finally, the third part required

a record of both the examiner’s and the

observer’s rating, as well as a general

assessment of the examiner’s communicative

competence as interlocutor made by the

observer. This had been defined in the

Observers’ Instructions

manual to

avoid subjective interpretation of the term

(which had occurred in the previous project)

and to enhance consistency in the

understanding of its meaning.

|

Candidate A |

PART 2:

communicative competence –

behaviour – body language |

Candidate B

|

|

(TICK

√) |

1. Did the Examiner use the

appropriate communicative

strategies? |

(TICK

√) |

|

|

a. S/he was polite, friendly and

welcoming, making the candidates

feel comfortable. |

|

|

|

b. S/he was too supportive. |

|

|

|

c. S/he lacked eye contact. |

|

|

|

d. S/he was not at all helpful

(when s/he should be). |

|

|

|

e. S/he appeared strict or

distant or stiff or indifferent. |

|

|

|

f. S/he looked shy or lacking

facial expressivity. |

|

|

|

g. S/he didn’t use any

conversational signals or

appropriate body language. |

|

|

|

h. S/he was too loud (in a

discouraging way). |

|

|

|

i. other (Please specify)

|

|

|

YES |

NO |

2.

Do you think that the

interlocutor’s communicative

competence/ behaviour/ body

language influenced the

candidate’s language output in

any way? If you circle YES, please indicate if s/he

made things easier or more

difficult for the candidate and

provide any useful comments

___________________________

_________________________________________ |

YES |

NO |

Table 11: Questions related to behaviour and

body language and their influence of the

candidate’s language output

The results from the analysis of the forms and

reports will be

presented in Section 5.2.

6. Data collected and

project results

6.1 Phase 1: The November

2005 observation

The outcomes from the recording, analysis and

interpretation of the information collected

through the November 2005 observation forms

proved to be valuable and

covered many aspects of the oral test.

6.1.1 Issues of organisation

It became obvious that there were cases of

deviation from the suggested procedure, e.g.

late arrival of examiners, lack of the right

facilities, and

limited time for preparation. These deviations

suggested that there was still room for

improvement in the area of organisation, and

this was stressed in a report sent to the

Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs.

For instance, a

list of candidates’ names should be given to

examiners before the exam begins, as it is

very important that changes should be

made

if an examiner knows any of his/her

candidates personally (especially in the

provinces). In addition, by preparing the

list in advance, candidates of similar age

can be paired up wherever possible. This is

very significant in terms of its effect on

the examiner’s choice of task,[10]

as well as on the language output,

especially in the C1 oral test, where the

candidates are asked to carry out a

collaborative task. Phase 1 of the project

revealed that this list had not been

prepared beforehand in many centres.

It is also worth mentioning that the observers

were welcomed both by the organising committees

and the examiners. Although the observation

project was newly administered, it appears that

the examiners felt more comfortable in the

presence of the observers

while they were preparing for the oral test, as

the observers could be consulted about issues

related to the procedure and also help with any

problems with the test material. Only in a few

cases did the presence of the observer in the

examination room cause anxiety for the

examiners; anxiety which was, however, soon

overcome.

6.1.2 The oral test procedure

With regard to how the oral test was

conducted by different examiners, the

results were particularly interesting. As

far as the seating arrangements were

concerned, there were cases in both levels

where the seating had not been arranged

according to the guidelines.

In connection to the examination itself and

the role of examiners as interlocutors, a

variety of issues came to light. The

observers were required to give a general

assessment of each interlocutor in

terms of his/her communicative competence,

choosing between Excellent, Very Good,

Mediocre and Poor, while Good

was also added by some observers, who could

not decide between Very Good and Mediocre.

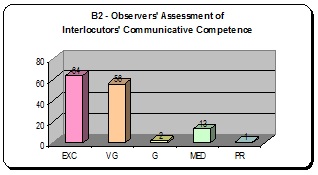

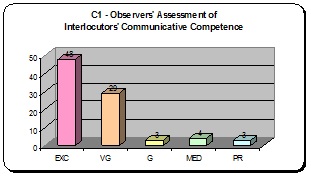

Charts 1 and 2 show the

results for both levels.

Chart 1: Assessment of interlocutors’

communicative competence at

B2 level (November 2005)

Chart

2: Assessment of interlocutors’

communicative competence at

C1 level

(November 2005)

It should be noted that

this is a very general assessment of the

examiners’ competence and cannot be regarded

as 100% valid, because the concept of

communicative competence was interpreted

differently (than anticipated) by individual

observers. This means that there were

somewhat varied criteria applied for the

choice of each characterisation. For

instance, communicative competence

was interpreted by some as language

competence. The latter is a significant

element and must be looked at separately as

a factor which can potentially prevent the

examiner from examining again or from

examining at advanced levels (C1 and C2). As

far as the examiner’s competence in conducting the exam is concerned, it can

be improved through training, as examiners

must continually be trained on how to

conduct the test by strictly following the

detailed guidelines regarding both the

procedure and the rules of conduct set by

the test designers. Examiners can also be

assessed on their performance, given

feedback and trained again, if necessary, or

kept informed on any changes or developments

in the nature of the examination.

Moreover, the observation

form involved 14 questions for the B2 level and

seven for the C1 level in relation to the

guidelines on the examination

procedure. Table 12 below presents the

questions, already included in Table 7, which

concern examiner competence in conducting the

test procedure. It also presents the relevant

questions from the C1 observation form.

|

B2 |

|

Activity |

Question |

|

1

|

3. |

Did the Examiner ask the candidate

2-4 questions from 2-4 different

categories? |

|

4. |

Did s/he take into account the

candidate’s age and other relevant

factors when s/he chose the

questions? |

|

2 |

8. |

Does the Examiner ask different

candidates to start first?

|

|

9. |

Did s/he take into account the

candidate’s age and other relevant

factors when s/he chose the photo(s)? |

|

10. |

Did s/he take into account the

candidate’s age and other relevant

factors when s/he chose the task? |

|

11. |

Did s/he use the rubrics provided?

(If you say no, it means s/he used

his/her own rubrics) |

|

15. |

Did s/he give (a) different photo(s)

to each candidate? |

|

16. |

Did s/he assign a different task to

each candidate? |

|

3 |

19. |

Did s/he start with a different

candidate each time? |

|

20. |

Did the Examiner take into account

the candidate’s age and other

relevant when s/he chose the text? |

|

21. |

Did the Examiner take into account

the candidate’s age and other

relevant factors when s/he chose the

task? |

|

22. |

Did s/he use the rubrics provided?

(If you say no, it means s/he used

his/her own rubrics) |

|

24. |

Did the Examiner use a different

text with each candidate? |

|

25. |

Did the Examiner assign a different

task to each candidate? |

|

C1 |

|

Activity |

Question |

|

1 |

3. |

Did the Examiner ask the candidates

one opinion question? |

|

4. |

Did s/he take into account the

candidate’s age and other relevant

factors when s/he chose the

question? |

|

2 |

8. |

Did the Examiner explain the

procedure for this activity using

the wording of the instructions

given in the examiner pack?

|

|

9. |

Did s/he take into account the

candidate’s age and other relevant

factors when s/he chose the texts? |

|

10. |

Did s/he take into account the

candidate’s age and other relevant

factors when s/he chose the task? |

|

11. |

Did s/he use the rubrics provided?

(NO means s/he improvised, used

his/her own rubrics) |

|

15. |

Did s/he carry out Activity 2,

according to instructions?

|

Table 12: Questions related to the

examination procedure at B2 and C1 level

The percentage of

deviation from the instructed procedure was

3% for B2 and 8% for C1, which do not seem

to be significant but show the existence of

variation and raise concerns about the

reliability of the test. In addition, the

percentages of unnecessary interferences or

interruptions and changes to the rubrics

(which are considered separately below)

should also be added to the aforementioned

percentages since they are regarded as types

of deviation from procedure. Table 13

comprises only the relevant questions for

both levels (for B2 only, the same questions

have already been presented in Table 7.

For these questions there was also space

available for comments and explanations.

|

B2 |

|

Activity |

Question |

|

1 |

5. |

Did s/he interfere in any way or

interrupt the candidates while

they were trying to talk?

|

|

2 |

12. |

Did s/he use the exact words of

the rubrics? (If you say no, it

means that s/he accommodated to

the candidates) |

|

2 |

14. |

Did s/he interfere in any way or

interrupt candidates? |

|

3 |

23. |

Did s/he use the exact words of

the rubrics? (If you say no, it

means that s/he accommodated to

the candidates) |

|

C1 |

|

Activity |

Question |

|

1 |

5. |

Did s/he interfere in any way or

interrupt the candidates while

they were trying to talk?

|

|

2 |

12. |

Did s/he use the exact words of

the rubrics? (If you say no, it

means that s/he accommodated to

the candidates) |

|

2 |

14. |

Did s/he interfere in any way or

interrupt candidates? |

Table 13: Questions related to

interferences/interruptions and changes to

the rubrics

at B2 and C1 level

Thus, with regard to interferences and

interruptions, the percentage reached 18% for

B2, and 16% for C1 in total. Since the observers

were also required to

keep track of and note down different types of

interferences and interruptions made by the

examiners, several categories came to light. For

example, examiners interfered or interrupted

against instructions in order to: a) make

corrections, b) clarify the task, c) supply one

or more words the candidate could not find while

talking, d) ask for or give an example, and e)

ask a seemingly irrelevant question. However,

there were cases included in the above

percentages in which it seems that interferences

or interruptions were correctly made, according

to instructions: a) to redirect the candidate

when s/he misunderstood something, b) to remind

the candidates to refer to the Greek text, and

c) to remind them of the task or of the need to

interact (C1). Especially for C1, there were

cases where, although there appeared to be a

need for interference or interruption, this was

not done.

As far as the incidence of changes to the

rubrics is concerned, the results were 12% for

B2, and 10% for C1. Again, observers listed

various types of changes. There were cases of a

synonym supplied (which can be acceptable),

changes of one or more words

in the rubric, partial use, explanation and

paraphrasing of the rubric, and addition of

further sub-questions (i.e. expansion of the

question).

The observers were also

asked to compare the examiners’ marks with

those they would assign if they were raters.

The percentage of agreement between observers

and examiners was 88% (as opposed to 22% for

disagreement) for B2. For C1, it was 74% (as

opposed to 26% for disagreement). Although

the percentages of agreement

are quite high, the amount of disagreement is

significant and points to the need for further

training of examiners in rating. It should also

be noted that the mark given by the observers is

characterised as ‘provisional’ because the

observers’ task of filling in the forms was

quite demanding, and their assessment of the

candidate could have been affected by this.

The form also included four questions

(see Table 8), for both B2 and C1 levels, in

relation to the examiners’ behaviour and

attitude, body language, eye contact, and

politeness. For questions 20(C1)/28(B2), space

was provided for the recording of relevant

comments and/or explanations. The results are as

follows:

For B2, 91% of the examiners received positive

ratings in terms of their behaviour, as did 89%

of the examiners in C1. The observers

also recorded the lack of visual contact and the

absence of self-confidence, spontaneity or

expressivity as instances of unsuitable

behaviour or attitude. There were also

characterisations such as ‘distant’, ‘strict’,

‘loud’, ‘over enthusiastic’, ‘too friendly’ and

‘stressed’. These comments constituted 9% of the

B2 assessments, and 11% of the C1.

Finally, in addition to issues relating to the

examiners, the observers were also asked to

assess the candidate’s reaction to the

examiner’s discourse (i.e. the way s/he talked

and acted and the way s/he delivered the tasks).

For the B2 level, the results were as follows:

positive, 88%; indifferent, 11%; and negative,

only 1%. These results refer to all three

activities. For the C1 level, 92% of the

examiners received a positive

rating, 8% were rated as indifferent, while

there was no negative rating at all. These

percentages concern only Activity 1. In

connection with Activity 2 in C1, there was a

question on the effectiveness of the tasks, in

terms of whether they stimulated interaction,

negotiation and management of talk, and relaying

(rather than translation) of information from

the Greek text. The percentage of positive

ratings was 83% (as opposed to the negative,

17%), according to the analysis.

6.2

Phase 2: The May 2006 observation

Through the analysis of the May 2006 observation

data, it became clear that examiners sometimes

choose discourse practices which deviate from

the norms, as dictated by the exam designers,

and that there are detectable categories

of variation which can affect the candidates’

language output and the final rating of their

performance. Thus, the second monitoring project

confirms the findings of the first, seconds the

argument for the need to video-record the

examination procedures, and points to further

investigation through observation.

6.2.1 Issues of organisation

Since the May 2006 observation form focused on

the interlocutors’ conduct, organisational

issues were described in the reports sent by the

observers. Thus, it appears

that there were again cases of examiners

arriving late, limited time for preparation, and

interruptions of the examination procedure by

members of the committee.

Additionally, as was the

case in November 2005, the observers were

once more welcomed both by the organising

committees and by the examiners, even

enthusiastically in some cases. Once again,

the examiners felt more comfortable in the

presence of the observers while they were

preparing for the oral test, and they often

asked the observers questions connected to

the procedure.

In four cases, the presence of the observers in the examination centre

proved invaluable, as they were asked to

take the place of absent examiners.

6.2.2 The oral test procedure

It is worth pointing out

that the findings which came to light

through the analysis of the November 2005

observation forms were generally

confirmed.

This means that the types of deviation from

procedure through interferences,

interruptions and changes to the rubrics

made by the examiners, or the kinds of

examiner behaviour or attitude that were

recorded in November 2005 were also

found in the examiners’ behaviour in May

2006.

To begin with, through

Part 1 of the observation form (which was

divided into the three activities (B2) or

two activities (C1) that the examination

process involves) it was found that in B2,

Activity 1, the major problem was that there

were many cases (46%) in which the

interlocutors asked only two questions, as

opposed to the two to four questions they

had been instructed to ask (see Table 8,

question

1). It is also worth noting that

there were many cases where only one question was asked. It appears that this was

done either because the interlocutors had

allowed the warm-up questions to take too

long, or simply because they thought,

probably influenced by the C1 exam (where

there is only one question in Activity 1),

that one question would be enough. On the

other hand, the vast majority of

interlocutors (99%) did take into account

the candidates’ age and general profile when

they chose the questions (see Table 8,

Question 2). However, because in many cases

there were no warm-up questions, it cannot

be certain that the interlocutors had any

evidence of the candidates’ profile other

than their age and sex. In C1, Activity 1,

the major problem was that there was a

tendency by some interlocutors to expand the

initial opinion question by using additional

questions (13%) and/or to turn the activity

into a minimal conversation (9%).

In terms of the rubrics

given in the Examiner Pack, it

appears that 15% of the interlocutors in B2

and 9% in C1 changed or interfered with the

rubrics in all three activities. It appears

that examiners still need to be trained not

to deviate from standard procedure, which is

to use the rubrics exactly as they are,

without explaining, expanding, or preparing

the ground for them. Examples of such

interlocutor practices are: a) creating an

introduction to the actual questions, b)

changing one or two words in the rubric, c)

expanding the question or task, d) using

examples to facilitate comprehension of the

question, e) explaining the rubric or the

task with or without the candidate’s prompt,

f) supplying a synonym for a word without

the candidate’s prompt, and g) rephrasing

the question. There were also some cases

where interlocutors asked question(s) or

assigned task(s) which they had created and

which were not included in the Examiner

Pack. Finally, there were instances (6%

for B2, and 8% for C1) where the rubric was

repeated, with or without the candidate’s

prompt. This is the only action acceptable

within the examination procedure rules.

Concerning the ways in

which the interlocutors interrupted the

candidates or interfered with their language

output while

they were performing the

activities (see Table 8, questions 4 and 5),

there were cases (17% for B2 and 10% for C1)

where the interlocutors: a) made additions,

b) asked a seemingly irrelevant question, c)

supplied one or more words the candidate was

unable to find, d) made corrections, e)

expanded the task, f) tried to explain the

task, g) commented on what the candidate had

said, h) asked questions to keep the

candidates going, and i) participated

actively in the discussion. There were also

instances where the interlocutors repeated

the question, or part of it, redirected the

candidates because they had misunderstood

something, or repeated the candidates’ last

words to help them continue, all three of

which are the only actions acceptable within

the examination procedure rules. Moreover,

there were also cases where the

interlocutors asked questions like, ‘Do you

have anything else to add?’ or ‘Is there

anything else you want to say?’, which have

not been evaluated in terms of their

influence – whether positive, negative or

non-existent – on the language output, and

remain an object for research.

Finally,

especially for C1, interlocutors sometimes

interrupted candidates to tell them that

they were not supposed to translate or that

they did not need to use all the information

from the text(s). The need for such types of

interventions can only be explained

intuitively and from personal experience: a)

there are still candidates who are not fully

aware of the KPG oral test procedure and the

skills it involves, and b) more formal

instructions (i.e. interlocutor frames[11])

should be used consistently when explaining

to candidates or simply reminding them of

every step of the procedure. This matter is

still in need of further research.

Again for C1, there were more cases of

acceptable actions within the

guidelines for the examination procedure. There

were instances where the interlocutors: a)

repeated the question or part of it, b)

redirected the candidates because they had

misunderstood something, c) reminded them to

refer to all the texts, d) reminded them that

they had to interact, e) reminded them of their

task or goal, and f) helped one candidate

continue by repeating his/her last words.

In relation to the question whether the

different kinds of changes

and interferences or interruptions in all

activities influenced the candidates’ language

output (see Table 10), the results were as

follows.

For B2, 55% of the observers answered YES, while

36.5% answered similarly for C1. According to

the observers’ comments, it appears that

interlocutor interventions helped the candidates

produce more output, or generally

made it easier for them to answer in many cases.

In some other cases, however, they made it more

difficult, as continuous interruptions caused

candidates to feel more stressed and did not

seem to allow them to produce as much output as

they might have been able to.

The observation form also

included one question on what the observers

would do as raters in cases where there were

many changes or

interferences and the language output appeared

to be thereby influenced. This question was

either not understood or ignored by most of the

observers, although it had been previously

explained. Those who did understand it stated

that any influence on the language output would

be taken into consideration accordingly.

Part 2 of the form (see Table 11) concerns the

general behaviour of the interlocutors, raising

issues of politeness,

friendliness and welcoming attitude, as well as

lack of eye contact, too much support or lack of

support when needed, strictness, stiffness,

indifference, lack of facial expressivity,

inappropriate body language, and very loud

(discouraging) voice.

When the forms were analysed, it was found that

all these attitudes and/or behaviours were

present to some extent in examiners, indicating

that there is a wide range of behaviour among

examiners in the university’s pool. It still

remains an object of research which of these

characteristics may influence candidates’

language output. According to the observers’

comments, and as it can be easily predicted,

interlocutors who are friendly, polite,

welcoming and smiling generally make the

candidates feel at ease. Those who are strict,

distant, stiff, show indifference, or avoid eye

contact add to the already stressful procedure

of the oral test. Still,

the exact effect of an examiner’s behaviour on

the language output cannot be made evident

simply through the analysis of the observation

forms.

Finally, Part 3 of the

form was a brief rating of each candidate by

all three parties: interlocutor-examiner,

rater-examiner and observer, where the

observer’s mark is once more considered

provisional, due to the demands of the main task

s/he was carrying out. Still, a general

comparison can be made

between the two examiners’ marks and the

observer’s mark. The analysis showed that in the

majority of the observation forms, there were no

significant discrepancies during this phase.

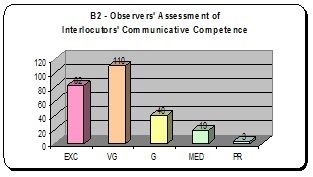

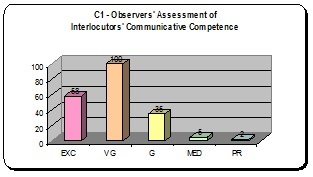

In this part of the form,

observers were also asked to assign a rating

for the interlocutor-examiner in terms of

her/his communicative competence on a scale

of Excellent, Very Good, Good,

Mediocre or Poor. The

analysis showed that the majority of examiners

are very good or excellent, but there are also

others who are rated as good, mediocre, and even

poor. Tables 16-17 show the assessments in both

levels.

Chart 3: Assessment of interlocutors’

communicative competence at

B2 level (May

2006)

Chart 4: Assessment of interlocutors’

communicative competence at

C1 level (May

2006)

7. Usefulness of the

findings and implications

The implications from the analysis and

interpretation of the monitoring project

data concern (and will continue to concern

so long as they are not addressed and dealt

with) the different parties responsible for

the KPG exam battery in various ways.

-

The

administrators need to address

organisational problems which seem to be

undermining the preparation for the

examination procedure.

-

The designers

and developers should be able to organise

more seminars and further train examiners

both as interlocutors and as raters.

-

Research should

continue in order to determine to what

extent deviation from rules and

instructions, i.e. any violation in the

effort towards consistency, affects the

candidates’ language output.

-

Video recording

of examination sessions can prove an

efficient tool in such an investigation, and

it should become part of any future plans.

Until that becomes possible, further

research through observation can be used to

yield reliable and valid results.

The results and implications from the analysis

and interpretation of the KPG November 2005 and

May 2006 observation forms give substantial

evidence of the value of such schemes for the

KPG examination system, as well as any other

formal certification system.

There are plans to support the findings from

observations with more detailed studies and

analyses of the language output produced during

examination sessions. For example, investigation

of the discourse practices the examiners use and

the way these may influence the candidates’

language performance can contribute to

discovering and eliminating factors which may

undermine the validity and the reliability of

the oral test, which is a priority of the KPG

examination system.

Endnotes

[1]

The project is being carried out

under the supervision of Professor

B. Dendrinos, Director of the RCeL,

who is responsible for the

preparation of the KPG exams in

English and Head of the English KPG

Research and Exams Development Team

(henceforth English Team). I wish to

express my sincere thanks to her for

helping me organise the present

study and for editing this paper. I

also wish to thank Dr Evdokia

Karavas, Assistant Director of the

RCeL, who is responsible for the

training of oral examiners and

script raters.

[2]

Many of these issues, plus that of

oral task content validity, are

being addressed with other ongoing

research projects. One of these

seeks to find out what examiners

think about the tasks and the way

the oral test has

been organised.

After every exam administration,

examiners are required to fill in a

Feedback Form which asks them

to explain a) which of the tasks

worked well for them, which did not

and why, and b) if they encountered

any problems during exam

administration.

[3]

My own PhD research also focuses on

Interlocutors’ discourse practices and

the ways these practices may affect the

candidates’ language output and draws

data from this monitoring project.

[4]

For an account of different studies

see Allwright 1988;

for the

COLT Observation Scheme see Spada & Frölich 1995; Cook 1990; and

Spada 1990 among others.

[5]

Only the November 2005 and the May

2006 phases, processes, means and

results are described within the limits

of the present article,

although four

more formal phases have been conducted

to date: May and November 2007 and

May and November 2008, which will be

presented elsewhere in the future.

[6]

The choice of examination centres

was based

on the number of examiners

and candidates assigned to the centres. The aim was to cover

centres all over Greece, but those

which had more examiners and

candidates were preferred as they

were expected to yield more results.

[7]

Having been given the opportunity to

prepare the new observation form and

conduct the seminar was a valuable

experience, especially since I

had

the help of Prof. Dendrinos and Dr

Karavas, as well as that of Dr

Drossou, Research Associate at the

RCeL.

[8]

These are strict guidelines which

describe the course of action to be

followed by the examiners in detail,

e.g. how to explain the procedure

to candidates, how to deliver tasks, and

in which cases to intervene.

[9]

Observers were advised to observe

each examiner

twice, i.e. with two pairs of

candidates, and had to use a new form

the second time they observed an

examiner.

[10]

The examiners are instructed to

consider the age and profile of

candidates when choosing questions,

tasks, photos and texts.

[11]

Interlocutor frames are defined as

predefined scripts

which have been provided by the exam

designer and are to be naturally recited

by the examiner in between the delivery

of questions or tasks so as to explain

to the candidate what each part of the

exam entails.

[Back]